By: Allison Williams

By: Allison Williams

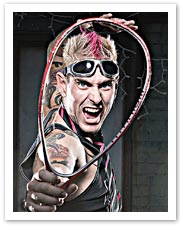

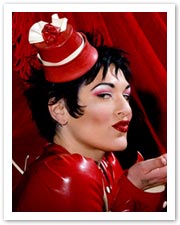

“Make kids cry,” the client says, and he’s only half-joking so I take him at his word. We open Ghost Circus with a trapeze artist splayed on the floor as if she’s fallen from the still-swinging apparatus. We perform a ‘heart transplant’ in which we sleight-of-hand-out a  real (pig’s) heart from another performer and replace it with an alarm clock. The ringmaster makes a balloon animal, and goes to present it to a kid—at which the Scary German Doctor interrupts, announcing, “That dog hasn’t had its shots!” and stabs it with a hypodermic, exploding the balloon in the kid’s lap. The kid cries. And I, dressed in ripped fishnets as Creepy Nurse #1, pull out a slate and make another tick mark under CRYING CHILD while the audience laughs.

real (pig’s) heart from another performer and replace it with an alarm clock. The ringmaster makes a balloon animal, and goes to present it to a kid—at which the Scary German Doctor interrupts, announcing, “That dog hasn’t had its shots!” and stabs it with a hypodermic, exploding the balloon in the kid’s lap. The kid cries. And I, dressed in ripped fishnets as Creepy Nurse #1, pull out a slate and make another tick mark under CRYING CHILD while the audience laughs.

I like it when the client lets us write the show.

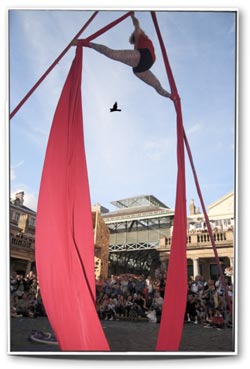

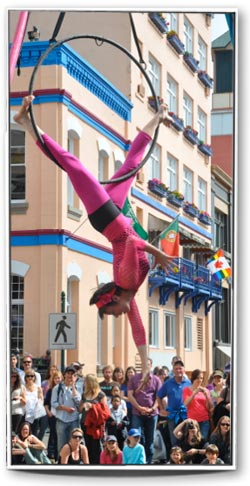

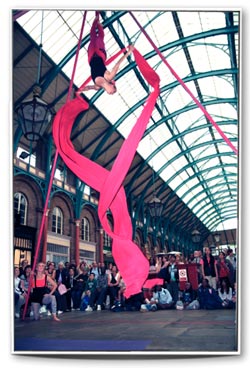

Mostly, being an event aerialist is about pleasing the client. I don’t work in a tent, or swing over a net, or live on a train. I wrap myself up in fabric over the buffet while suits ignore me and eat shrimp. I appear from a trapdoor in the ceiling and perform a routine with a Rolex on my upper arm, then fast-slide down and hand the Rolex to the Salesman of the Year. Bomb sweeps and bag searches before the heads of state arrive at International Water Week, Singapore. Sidelong looks at our skintight costumes in Dubai Festival City. Slippery hands—we forgot our sticky rosin—for Citibank Asia in Barcelona. It’s fancy and flashy and spandex-y and false-eyelash-y but it’s not wild and free. If you want to be wild and free, be poor. Or work the street.

Mostly, being an event aerialist is about pleasing the client. I don’t work in a tent, or swing over a net, or live on a train. I wrap myself up in fabric over the buffet while suits ignore me and eat shrimp. I appear from a trapdoor in the ceiling and perform a routine with a Rolex on my upper arm, then fast-slide down and hand the Rolex to the Salesman of the Year. Bomb sweeps and bag searches before the heads of state arrive at International Water Week, Singapore. Sidelong looks at our skintight costumes in Dubai Festival City. Slippery hands—we forgot our sticky rosin—for Citibank Asia in Barcelona. It’s fancy and flashy and spandex-y and false-eyelash-y but it’s not wild and free. If you want to be wild and free, be poor. Or work the street.

There’s festival street and cold street. When we’re not doing corporate events, we’re a festival show. Our 25-foot tripod rig takes too long to set up, we don’t want to have to ‘move along, please’ for cranky local cops. But at a festival, setting up is part of the show. Street performing is not casual. It is tightly scripted—I am on stage from the moment I step onto the pitch, the twenty or thirty-foot circle of pavement assigned on the schedule,  bitched about in the morning (location, location, location), and made the best of in the afternoon. Turn the amp on, music makes it our space. Set the expectations early—you will make a circle, strangers; you will stand at the rope, children; you will laugh, skeptics; you will be safe here, volunteers. We will treat you well, if you come on stage. We will make you a winner. At the end, we will pass the hat, and you, having followed our orders for thirty minutes, having had a better time than you thought at a more professional-looking show than you expected, will give. When people come up after the hat pass and ask, “So, is this your real job?” they mean How much money do you make? and that’s the question I answer: I used to be a professor. This pays better. No benefits, but I don’t have to sit in committee meetings, so it’s a tradeoff. Then they laugh and everything is cool.

bitched about in the morning (location, location, location), and made the best of in the afternoon. Turn the amp on, music makes it our space. Set the expectations early—you will make a circle, strangers; you will stand at the rope, children; you will laugh, skeptics; you will be safe here, volunteers. We will treat you well, if you come on stage. We will make you a winner. At the end, we will pass the hat, and you, having followed our orders for thirty minutes, having had a better time than you thought at a more professional-looking show than you expected, will give. When people come up after the hat pass and ask, “So, is this your real job?” they mean How much money do you make? and that’s the question I answer: I used to be a professor. This pays better. No benefits, but I don’t have to sit in committee meetings, so it’s a tradeoff. Then they laugh and everything is cool.

They’re not paying us for the show. No-one is. I get a call from a woman putting on The Nutcracker ballet in Chicago. She tells me about the dancers flying in from Brazil, the press the show is going to get, and I know where this conversation is going, I’ve had it before. There is no “good exposure.” People die from exposure. I cut her off and tell her the two aerialists will cost $2500.

They’re not paying us for the show. No-one is. I get a call from a woman putting on The Nutcracker ballet in Chicago. She tells me about the dancers flying in from Brazil, the press the show is going to get, and I know where this conversation is going, I’ve had it before. There is no “good exposure.” People die from exposure. I cut her off and tell her the two aerialists will cost $2500.

She says, “But it’s only five minutes!”

I have heard this before, I am nearing retirement from this field and I am tired of this shit. I do not make nice to get the gig. I say, “The performers will drive six hours to get to you. They will spend an hour rigging, then do four hours of rehearsal with your dancers. They will stay overnight in Chicago, away from their homes. They will show up at the theatre and do an hour of stretching, an hour of technical rehearsal and an hour of makeup. They will wait through your two-hour ballet. Then they will take down their rigging and drive six hours home. Once you pay us for all that, we’ll throw in the five minutes for free.”

She says weakly, “Please send a contract.”

I’m a fucking brilliant director. I’m a merely average aerialist. One who has nonetheless made a living in my field for fifteen years. My heart has broken over performers quitting, over firing them for drugs, weeping when they leave me to get married.

I’m a fucking brilliant director. I’m a merely average aerialist. One who has nonetheless made a living in my field for fifteen years. My heart has broken over performers quitting, over firing them for drugs, weeping when they leave me to get married.

I don’t want to let it go. I have to let it go. Performing and directing is 80 hard hours a week. There is no time to write. My rotator cuffs aren’t getting any younger. It’s harder to wear identical spandex next to my 21-year-old partner fresh out of circus school. She’s next. She gets the company now, to soar and screw up, like I did, but I am only a phone call away and I want her to win this game. I won, and the prize is quitting.

Here’s what being a writer means: considering every word. Here’s what being a street entertainer means: considering every word and every inflection and delivery and adjusting them on the fly to the weather and the time of day and the level of drunk and the local morality. Telling jokes that sound like silly jokes to kids and dick jokes to adults. Bringing up volunteers who are terrified we will humiliate them but too macho to refuse, then celebrating them as heroes. Undoing the work of a hundred shitty street performers who made their audience members feel like crap. And after all that, putting one word after another—on paper! Where I will revise it perhaps thirty times instead of a thousand and it will be done!—is easy.

________

This piece originally appeared in “Writers’ Other Jobs” at The Writers Bloc. http://thewritersbloc.net/running-away-circus

________