By: Rick Lewis

By: Rick Lewis

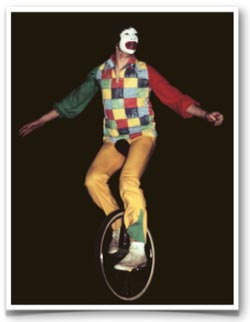

The first time I remember seeing a unicycle was on the floor of a Toys ‘R’ Us store. I was completely captivated by the novelty of this circus prop and curious about what it would be like to ride it.

Responding to my fascination, my parents purchased it for me. I gradually learned to ride it while circling the ping-pong table in our family room and used the table to support myself as I traveled around its perimeter.

Responding to my fascination, my parents purchased it for me. I gradually learned to ride it while circling the ping-pong table in our family room and used the table to support myself as I traveled around its perimeter.

I can remember the frustration I felt in my initial efforts to ride this unique machine. It seemed impossible to me that one could ever learn to balance on a unicycle. The breakthrough I eventually had in the learning process occurred when it dawned on me that it was impossible. I finally understood that the only thing I could do on the unicycle was to allow myself to fall—to intentionally give up my balance and then chase that elusive balance point by pedaling toward it.

Metaphorically, this represents the process of moving toward excellence, which is always a balance between doing nothing at all and going too far. Before we can learn how much is  just right in relationship to making efforts, we have to go too far and cross the line. It’s only after we have fallen down a few times—or many—that we develop an exacting sense of how hard to lean toward our goals.

just right in relationship to making efforts, we have to go too far and cross the line. It’s only after we have fallen down a few times—or many—that we develop an exacting sense of how hard to lean toward our goals.

The process of unicycling is in fact nothing but the continuous act of falling and attempting to recover from the fall. If one does not “fall” on the cycle, it’s impossible to move forward, since it is this seeming loss of balance that initiates any forward progression. Such is its nature. Anyone who is interested in growing toward excellence must seek a degree of imbalance to allow for forward progress. Our growth and progression is the activity of hovering at the point where we’re just about to cross the line.

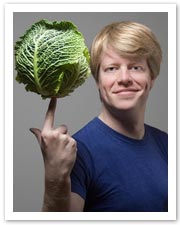

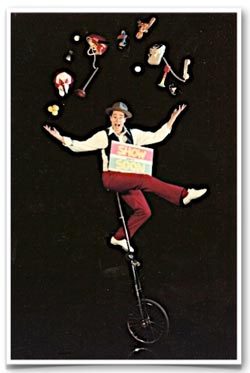

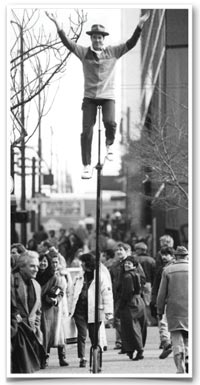

Once I had developed some proficiency at riding that first little unicycle, I took it out onto the streets of our neighborhood. I received a fair bit of attention and was satisfied with this for a few years. Then I learned that taller versions existed.

The next step was the order of a six-foot unicycle. The conflict between how badly I wanted to try riding it and the fear of falling was vivid in my experience the first time I sat on it. The consequences of taking a spill from this height were obviously more significant, but the principle was the same: lean first, fall forward, and ride as a result.

The next step was the order of a six-foot unicycle. The conflict between how badly I wanted to try riding it and the fear of falling was vivid in my experience the first time I sat on it. The consequences of taking a spill from this height were obviously more significant, but the principle was the same: lean first, fall forward, and ride as a result.

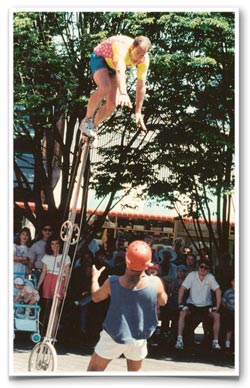

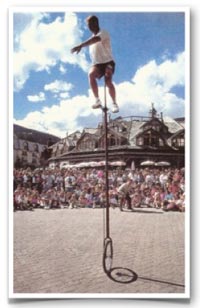

Years later, chance circumstances provided me with the opportunity to ride a unicycle that was twelve-feet tall. An acquaintance of our family had called to tell us about a boy she knew who was also a unicyclist. After he had developed some skill on a six-foot cycle like the one I had, his parents had supported him to order a custom-made twelve-foot unicycle that had recently been shipped to him from across the country.

So far, our friend reported, he hadn’t been able to ride it. She wondered whether I might be able to help, and so a meeting was arranged.

I remember standing in the driveway of this boy’s home when he brought the machine out of his garage and stood it up. He began describing how afraid he had become at the idea of getting on. He didn’t know how to overcome his fear. I tried to encourage him with the excitement I experienced just from setting eyes on it. I asked him if he had tried riding it at all. He said that he’d only sat on it while holding onto a second-story window of his house.

I remember standing in the driveway of this boy’s home when he brought the machine out of his garage and stood it up. He began describing how afraid he had become at the idea of getting on. He didn’t know how to overcome his fear. I tried to encourage him with the excitement I experienced just from setting eyes on it. I asked him if he had tried riding it at all. He said that he’d only sat on it while holding onto a second-story window of his house.

We climbed a ladder to the roof of his garage, which was the only available way to mount the thing. I hoped he would actually push away from the house and give it a try. Once we were at the edge of the roof looking down, however, I understood completely what had stopped him. Instead of looking up at the seat of the cycle from the safety of the ground and thinking, I could do that, I was now looking at the distant pavement fifteen feet below and thinking, I could die doing that. This was no mere parlor trick. It was a serious undertaking.

After an hour of trying to get on it, the steam of any remaining enthusiasm gone, he said, “I just can’t do it. You can try it.” In truth I was now as scared as he was. A big part of me still wanted to, yet I was so frightened by the potential hazards of the stunt that I was shaking and distracted by all the excess adrenaline. I decided that my best option was to practice falling first so I’d know that when the moment came I could handle it. I pointed the towering machine toward my friend’s front lawn instead of the pavement of the driveway, hopped up on the seat, and promptly pitched myself forward off balance and headed onto the grass before I had time to work myself into any more of a state about it.

After an hour of trying to get on it, the steam of any remaining enthusiasm gone, he said, “I just can’t do it. You can try it.” In truth I was now as scared as he was. A big part of me still wanted to, yet I was so frightened by the potential hazards of the stunt that I was shaking and distracted by all the excess adrenaline. I decided that my best option was to practice falling first so I’d know that when the moment came I could handle it. I pointed the towering machine toward my friend’s front lawn instead of the pavement of the driveway, hopped up on the seat, and promptly pitched myself forward off balance and headed onto the grass before I had time to work myself into any more of a state about it.

My feet and legs stung from the impact, but the actual experience of falling prepared me to ride, whereas a purely imaginary fall had been messing with my head and preventing me from focusing. Our attempts to be certain that we won’t make a mistake, fall, or err are often counterproductive to our aim. Sometimes intentionally crossing the line and making a mistake in a controlled setting helps diffuse the potential for our fear to distract us.

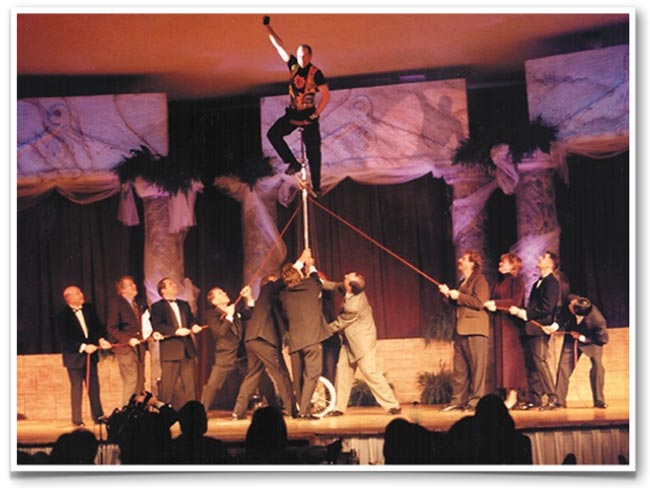

The plan worked. A few minutes later I was pedaling the unicycle down the driveway and out into the street, my head fifteen feet in the air, my eyes wide, and feeling on top of the world. I left his house that day the new owner of the machine and have used it for the finale of my performances ever since.

The plan worked. A few minutes later I was pedaling the unicycle down the driveway and out into the street, my head fifteen feet in the air, my eyes wide, and feeling on top of the world. I left his house that day the new owner of the machine and have used it for the finale of my performances ever since.

Our willingness to lose our balance and cross the line frees us to experience and explore our curiosity.